Date: January 11, 2026

Place: Boyne Valley Provincial Park, near the town of Mono, and some 20 minutes’ drive from Orangeville.

Weather: fairly fresh deep snow, cold

References:

– [1] ‘Mammal Tracks & Sign: A Guide to North American Species’, Mark Elbroch, Stackpole Books (1st Edit), 2003

– [2] ‘The Tracker’s Field Guide: A Comprehensive Manual for Animal Tracking’, James Lowery, A Falcon Guide (2nd Edit), 2013

– [3] ‘Bird Tracks & Sign: A Guide to North American Species’, Stackpole Books, Mark Elbroch, 2001.

Observations:

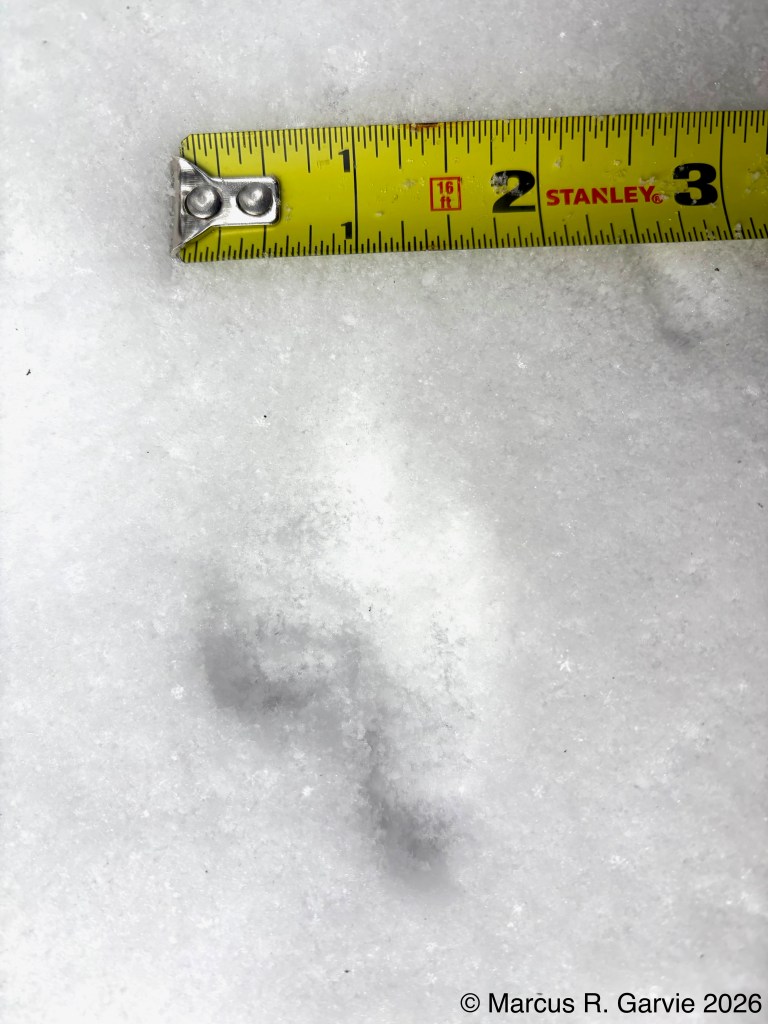

This was the second day the Tracking Apprenticeship group from Earth Tracks met in the Boyne Valley (I was unable to attend the first day). We had a rich day of wildlife tracking and observed tracks and sign of many species. Initially we saw many excellent tracks of Ruffed Grouse:

One of the things I learned is that these tracks form what look like arrows in the snow that point in the opposite direction of travel. This is because the hallux (toe 1) is much smaller than toe 3, while toes 2 and 4 point to the sides and forward, producing a typical anisodactyl track pattern. This is useful because, even when individual tracks are less clear than those shown here, the basic arrow shape is often still visible. When conditions are very poor, the pattern may reduce to a railway-like impression, with two parallel lines crossed by regularly spaced perpendicular marks (see the first picture above). The following measurements are from [3]

Track length: 1 5/8 – 2 1/4 in,

Track width: 1 3/4 – 2 3/8 in,

Trail width (walk/run): 3 1/4 – 10 1/2,

which is consistent with our observations, although the trail widths we found seem on the lower end.

We also came across amazing tracks of where a grouse landed, showing the tail feather impressions and the depressions where the feet landed:

We also found porcupine chew marks on Yellow Birch and tracks of a Red Squirrel. The porcupine had been feeding on the cambium layer of the bark, and the chew marks are very distinctive. I have included the tracks of a bounding Red Squirrel because, in this photo, the long toes of the front feet are easy to see and help distinguish it from a Gray Squirrel, in addition to the Red Squirrel’s narrower trail width.

We found deer tracks everywhere and discussed how to determine the sex of a deer from its urination pattern.

In the first photo above, the track has a distinctive hourglass shape, which is often seen in deeper snow. This occurs because a deer’s foot is narrower near the “ankle” and wider both above and below this point. This is a useful diagnostic feature for older tracks, when finer details are obscured. In the second photo, we interpreted the “messier” urination pattern as indicating a male deer, while the “cleaner” pattern in the third photo suggested a female. Another feature that can help distinguish sex is the position of the urine mark relative to the tracks. If the mark lies mainly behind the hind feet, it suggests a female; if it falls between the front and hind feet, it suggests a male. In our two photos above, however, there were so many overlapping tracks that this criterion was difficult to apply.

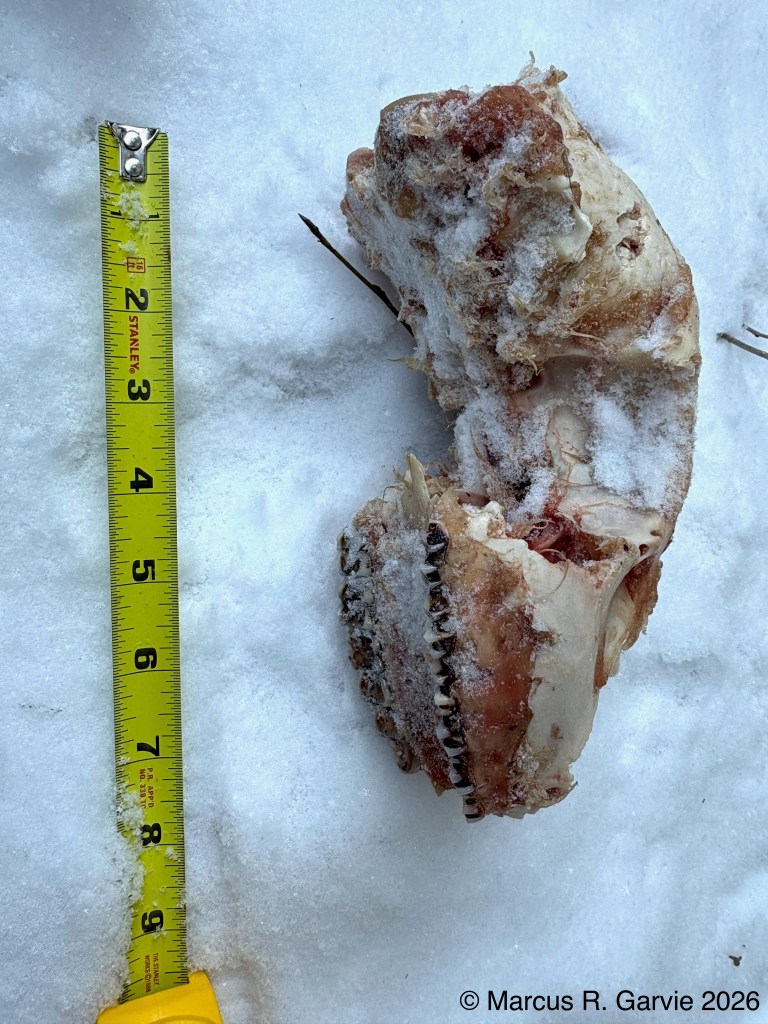

At one point, in a semi-clearing, we found the relatively fresh bones of a doe. We knew the deer had died within a few weeks because there was still red blood on the skull.

Observe the eight incisors on the lower jaw bone (deer have no incisors on the upper jaw). In the third photo, we see a front leg bone; the hoof was missing, and the bone appeared to have been broken open, likely by a coyote. In the fifth photo, we can see the teeth of the upper jaw. Other members of the tracking group spent some time estimating the deer’s age based on tooth number and patterns of wear, and concluded that the doe was about 5½ years old. I need to learn how to do this myself, as well as the names of the main bones of a deer. The humerus is the upper front-leg bone from shoulder to elbow, the radius is the main weight-bearing bone of the lower front leg, and the ulna is reduced and partly fused to the radius in deer (readers, please correct me if this isn’t accurate!).

Periodically, we found Snowshoe Hare tracks. According to [1], the hind tracks can be up to 5 inches wide when splayed. The tracks we observed were not splayed, so the hind prints were much narrower. I estimate the hind-track width in my photos to be about 1¾ inches, which is close to the upper end for a cottontail.

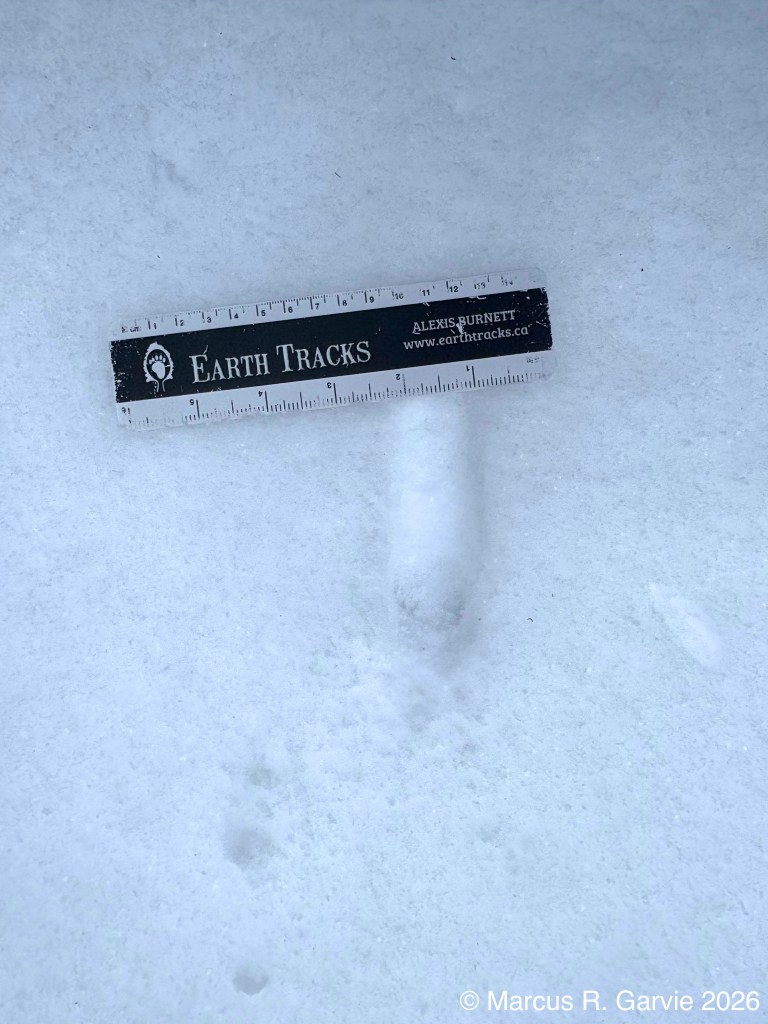

One of my intentions on this trip was to find the tracks of a weasel – either the Short or Long-tailed weasel. We were fortunate in finding the trail of what people thought was from a Short-tailed Weasel (aka Ermine):

The weasel is traveling in a 2 × 2 lope, with the hind feet landing where the front feet were, so each apparent pair of offset tracks actually represents four tracks. From my photos I make the following estimates:

trail width: 1 3/4, 1 1/4 inches

track length: 3/4 inch

track width: 1, 3/4 inches

Looking at these measurements and comparing them with those in [1], I think the tracks could also have been made by a Long-tailed Weasel, as there is some overlap in track size between these two species. Other trackers mentioned a mnemonic for remembering their preferred habitats based on the first letter of their names:

(S)hort-tailed weasel: prefers (S)olid ground

(L)ong-tailed weasel: prefers (L)iquid ground (i.e., areas near water)

However, after looking online at a variety of sites I was unable to find clear online evidence supporting this distinction, as both the Long-tailed and Short-tailed weasels are reported to occupy a wide range of broadly similar habitats, including both upland and riparian areas.

At one point during our outing, we found a hollowed-out tree where a broken branch exposed the interior. After pulling some of the apparent nest material out onto the ground, I was able to photograph the tiny, distinctive scat of a flying squirrel.

For the last part of the day we trailed coyotes. One of the trails was confusing because it had an unusual pattern of tracks. Some tracks seemed to partially register, or were in an odd pattern. The members of the group concluded that it was possiblke that the coyote had an injured leg. For much of the trails the canid was in a direct register trot.

We know this is a trot and not a walk because the stride here is about 22 inches [1]. In the next photo we have a pause/slow down with a possible looking to the right.

We wondered if we spooked the coyote as we found where it transitioned into a gallop.

The order of tracks from bottom to top is: RF, LF, LH, RH. In the next photo the coyote has sped up even more as the distance between the front feet is now greater then the distance between the hind feet in this group of four tracks.

We also found fresh scat (not frozen) and coyote beds. The beds are much rounder in shape and smaller (length 17 in) than the deer beds I have seen.

In the next photo we can see where the coyote came up to a large fallen tree and ‘put on the breaks’. All four feet show where it decided not to jump over the log and go around it instead.

Final thoughts:

The diversity and quantity of tracks and sign found in a single seven-hour period was remarkable. This greatly contributed to what trackers call “dirt-time” and gave me a wealth of knowledge that I hope to use in the future.

Leave a comment